Why our homes matter and what they mean to us.

For most of contemporary human experience, the idea of home has been defined by stability, familiarity, and comfort. In pragmatic terms, a house is a financial investment – a means to build equity and generational wealth for families. In emotional terms, a house conjures feelings of warmth and connection – a means to build memories that embellish and sustain our ideals. We build lives within its walls, forming bonds that get tethered to its structure over time.

Homes provide space for personal connection that no other space can provide. Our homes are vital to maintaining our sense of self, our sense of safety, and our sense of nourishment, centered on the basic need for privacy and family. Home provides respite from the stressors of the outside world as we endeavor to leave our strife elsewhere, preserving our sense of sanctuary.

How our homes are changing and where new and old functions are fitting within it.

The aspirational meaning of home changed drastically for most people in March 2020. Widespread lockdowns forced many to bring every aspect of their lives into their home. The chaos of conflicting activities began to compound and overlap, spilling into different mixtures of working, playing, learning, eating, and resting. Individuals and families were forced to accommodate all their professional and personal responsibilities and interests within a single bound space. After all, home was still the safest place we could be.

The notion of the home as a sanctuary began to subtly dissolve, as work infiltrated our bedrooms, kitchens, and basements. People had to assemble makeshift office spaces – a space within a space – to establish separation between work and family in any way, shape, or form. Homes became more subdivided to accommodate ad-hoc needs and the variety of tasks that each day would bring. Our homes transformed into multi-dimensional environments that allowed for both formal and informal adaptability and flexibility. Many maintained an optimistic view of their temporary accommodations, with an eye always on a return to “normal.”

As the pandemic has worn on, however, it has become clear that some of the overlap, particularly between home and work, would be here to stay. Many employers are incentivizing remote work, using it as a recruitment tool, or to avoid losing workers to the Great Resignation (1). For those who can take advantage of the opportunity, home office set-ups are becoming permanent fixtures, adding flexibility and value for either the current homeowner or for prospective buyers.

Spaces are popping up as separate from the typical functions of the home and are curated for virtual interactions. Statement walls, flattering lighting, and ergonomic furniture have become features of home offices, adapting these spaces to our current needs. One specific trend that’s emerging is the outdoor workspace, an ancillary space that takes shape from reorganizing a patio and garden space to building add-on components for a certain degree of privacy and separation, especially for impromptu business meetings and client presentations.

Socioeconomic and cultural forces encourage stylistic adaptation as a curated home.

Even as we’re able to adjust our routines and as the compartmentalization of our homes becomes a long-term necessity, comfort has re-emerged as a priority. Our temporary accommodation of chaos has evolved into the reclamation of our feelings of sanctuary through a curated home. Short-term uncertainty can be used to discover an emergent orderliness with a high degree of personalization. As such, the meaning of home is evolving to reconcile our needs for sanctuary within a changing social and professional context. One emerging trend, maximalism, aims to help us wrangle these disparate influences while getting us back into our comfort zone (2).

Bold colors, clashing patterns, layered textiles, and lush houseplants lend an air of opulence to maximalism, which on the surface looks like every other design movement in recent history. It’s an aesthetic backlash – to over-consumption, to the formality of minimalism, to the infiltration of technology into our daily lives. It’s also a reaction to pandemic-imposed changes to daily routine and its immediate encroachment on our boundaries. Swift lockdowns and a gradual return to normalcy left us to reevaluate what truly makes us feel at home (3).

At its core, maximalism is the result of a grassroots movement, an anti-corporate method of proactive responsiveness to unavoidable chaos that addresses our need for self-expression and comfort amid austerity and uncertainty. Under the surface and inside the home, the reuse and reclamation inherent in maximalism supports the movement to a circular economy as well. Pandemic-driven deficiencies in the global supply chain have made this approach all but necessary and has ignited a generational shift from traditional consumption of the new and pristine, i.e., keeping up with the Joneses, to one built on democratized functionality, comfort, and safety.

And, we can add democratized circularity of materials and technology to the list. One company, Ecovative Design, thinks that the future of consumption will be circular using bio-engineered materials, ultimately tied to nature’s biological cycles (4). Made entirely from mycelium, one of the most prolific and opportunistic lifeforms found on our planet, Ecovative Design leads the way to a forthcoming fungi-made market. Mushroom home, anyone?

The growing necessity for enhanced functionality, wellness, and safety.

As our homes take on new dimensions of materiality and activity, providing optimized functionality, comfort, and safety is ever more desirable. This optimization is being framed around the need to reprioritize the importance of our mental and physical health. The emergent stylistic trend of maximalism has an inherent goal of elevating personal priorities and preferences that are catered to our overall well-being.

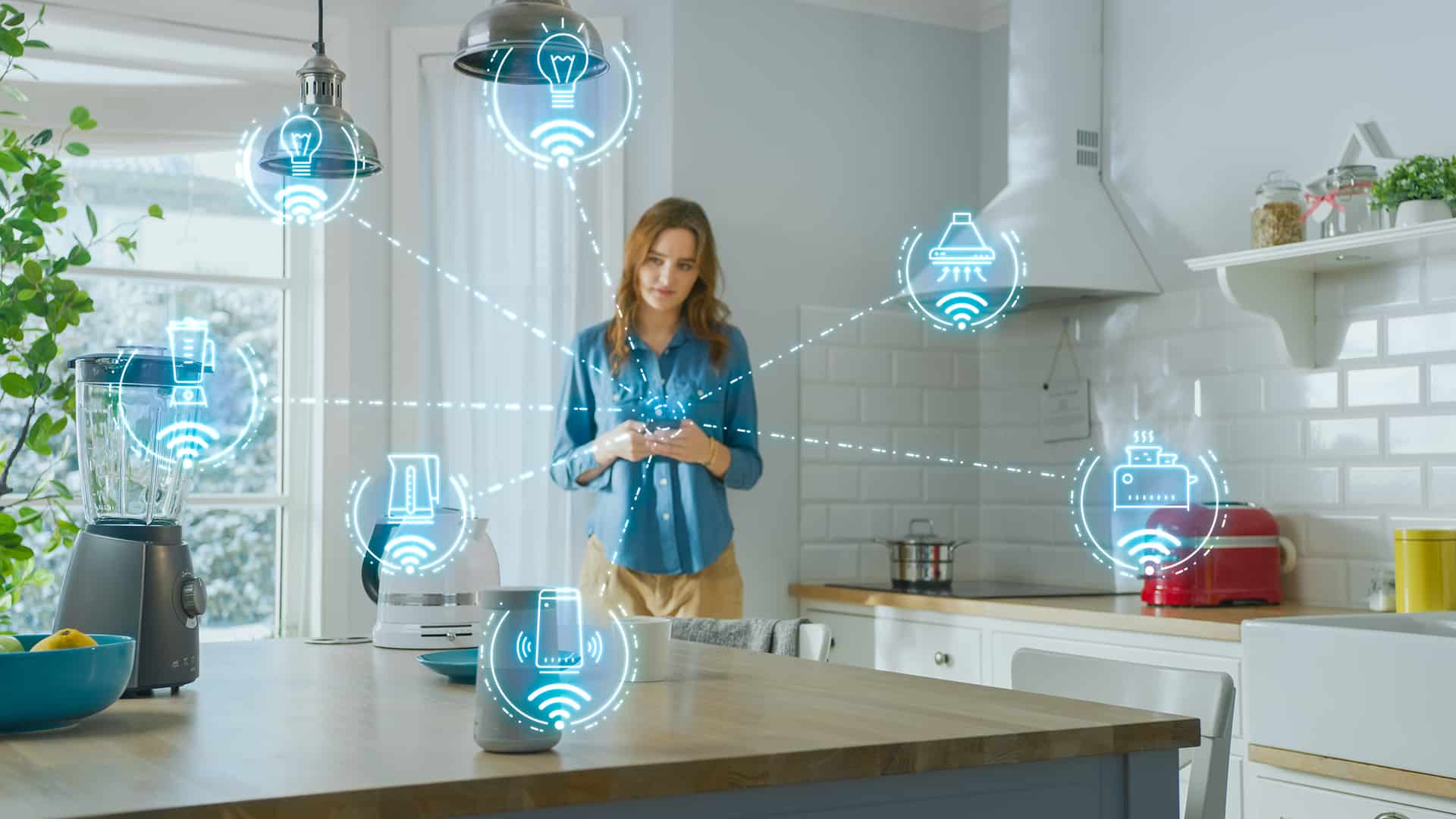

Imperfect design, another trend that is emerging and is philosophically connected to maximalism in its response to minimalism, attempts to reunite broken or severed materials in unique and personalized methods of reassembly. Reminiscent of the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery, known as kintsugi, imperfect design captures the necessity to celebrate breakage and repair as a part of the material’s history rather than making it invisible (5). As our technology becomes ever more invisible and integrated into our daily lives, can embracing imperfect design help repair our sense of togetherness within our homes as computers, smart phones and tablets constantly capture our attention?

Using maximalism as an aesthetic overlay, an optimized home becomes an integrated home where new technology meets old, circularity and recyclability meet longevity, and personal customization meets adaptability – all centered around multi-functionality and health. By being forced into multi-functionality, the home becomes a re-hypothesized “machine for living”, a phrase coined by Le Corbusier to push a technology-driven modernist aesthetic centered around optimized functionality devoid of decoration and opulence (6). But, with the concepts of maximalism in mind, the home becomes a “dynamic machine for healthy living” where many layers of activities and priorities intended to preserve our health, comfort, and safety are woven into our everyday spaces seamlessly.

High-performance homes with augmented functionality for sustained well-being.

As we began to rely more on the safety of home, concerns about cleanable surfaces and indoor air quality became a high priority, with consumers stocking up on cleaning products, filters, and freestanding air purifiers. Once ubiquitous, the concern for sanitized surfaces and purified air brought the advents of the sustainable building market into focus.

When paired with certification programs, such as those offered by the Passive House Institute (7) and the International WELL Building Institute (8), health concerns become great opportunities for enhancing our homes with technology and systems for high-performance design goals. And it pushes certain technology into hybridized integration with other household items, such as air purifiers that are also light fixtures or works of art simultaneously. The notion of multi-functionality becomes nested within the home from the top down.

The idea of two or more household items being bundled into one object or feature is an outcome of our dependence on technology. Younger generations are driving trends that are further optimizing and hybridizing technology, which can be viewed by some to be in opposition with the home being our sanctuary. With so much technology around us, can our homes work against our overall health? The answer to the question will continue to play out over time.

However, if we think of these technological integrations as augmentations of the home, we can bring mental and physical health into focus with built-in conveniences. These conveniences could allow for “autopilot” moments, giving us the freedom to focus without distraction or be less anxious while contemplating potential dangers. Indoor air quality monitors, high-efficiency air filtration and ventilation, circadian rhythm lighting, advanced real-time sensors, and healthy and environmentally friendly materials are some examples from the sustainable building sector that can give our homes a stronger sense of sanctuary and allow us to remove stress-related incidents from our daily lives.

Homes with a bigger purpose and responsibility.

Our homes function in new and myriad ways to support our individual health, but isolation, even in the comfort of our homes, can be detrimental to our mental health. A side effect of enduring the unforeseen conditions of this lingering pandemic is continued social disengagement and personal detachment from society. And as our homes kept us safe from the outside world, the outside world continued to have a big impact on our collective well-being.

Once the lockdowns were enforced, the home became centerstage in navigating the waters of existential contemplation, especially with unsettling news of lost lives and forgotten progressive steps pushing for equality and social justice. If technological progress continues to operate with the goal of improving and protecting human life by coupling difficulty with success or inability with ability, can our homes be a living example of recoupling common ground between people, people and nature, and people and policy?

Our homes provide safe spaces to have important conversations with loved ones and are a backdrop to the progression of our ideals and aspirations throughout our lives. The spaces we rent, purchase, or build reflect our values and can support or negate our personal priorities, no matter how hard we seek perfection. But life is imperfect. People are imperfect.

Even as we strive for perfection, new obstacles and challenges come into the fore with relentlessness. The dialectic between perfect and imperfect will never be decoupled from our roles and responsibilities as citizens, parents, and contributors to a better future. It’s a perpetual balancing act, and it’s woven into the fabric of our evolution. Our homes are an extension of that evolution. They give us the opportunity to engage in self-reflection and self-improvement as a long-term endeavor.

Footnotes

- Derek Thompson, “The Great Resignation Is Accelerating”, theatlantic.com, The Atlantic, Oct. 7, 2021, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/10/great-resignation-accelerating/620382/

- Mimi Montgomery, “Millennial Maximalism, the Design Trend That Explains Why So Many Younger People’s Homes Are Starting to Look Like Your Grandma’s Groovy 1960s Living Room, washingtonian.com, The Washingtonian, Feb. 2, 2021, https://www.washingtonian.com/2021/02/11/millennial-maximalism-the-design-trend-that-explains-why-so-many-younger-peoples-homes-are-starting-to-look-like-your-grandmas-groovy-1970s-living-room/

- Marni Jameson, “Home decor: Forget minimalism, maximalism is back”, eastbaytimes.com, East Bay Times, Oct. 28, 2021, https://www.eastbaytimes.com/2021/10/28/home-decor-forget-minimalism-maximalism-is-back/

- Ecovative Design, https://ecovativedesign.com

- Kintsugi, wikipedia.com, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kintsugi

- Le Corbusier, and Frederick Etchells. “Towards a New Architecture,” New York: Dover Publications, 1986. Print.

- Passive House Institute US (PHIUS), https://www.phius.org/home-page

- International WELL Building Institute (IWBI), https://www.wellcertified.com