This article, co-written by Carson Dinger, MS, of Texas Wesleyan University, was originally published in the April-June 2024 edition of the Planning for Higher Education Journal by the Society for College and University Planning (SCUP).

Collaborative planning for a residential housing transformation at Texas Wesleyan University ensured that the institution and its partners were responsive to the needs and aspirations of its stakeholders.

Throughout Texas Wesleyan University’s (TWU) expedited mini-master plan design process, we utilized integrated planning techniques to ensure all stakeholders were involved at the right time to align the university’s priorities: enhancing student life on campus by improving housing, dining, and an overall sense of community. Without strong interdepartmental partnerships, shared vision, and concessions made by all stakeholders at various points in the iteration process, a student housing and dining transformation project could never have been completed within the aggressive timeline laid out by the university.

The plan’s biggest challenges were not surprising: cost and proper phasing. TWU is a small, private institution with a limited endowment. That makes taking on multiple projects simultaneously difficult. Campus housing is self-liquidating, so the project can pay for itself quickly if the price point and construction costs are balanced. However, campus dining is more complicated. While it, too, can be self-liquidating, the payback takes longer due to myriad complex and unpredictable variables like supply costs and market demands. Designing mechanical, electrical, and plumbing (MEP); heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC); telecommunications; and other infrastructure into the projects in an integrated fashion is ultimately more cost-effective than designing and building separately. Making physical space available from the beginning comes at a slight premium, but the largest costs, equipment and underground utilities, can be phased.

SETTING THE STAGE FOR STUDENT LIFE IMPROVEMENTS

As TWU navigated the COVID-19 pandemic, the university reinforced its push for an increase in student retention. Considering the estimated 15 or more percent enrollment drop by 2025 predicted by Nathan Grawe (2023), the TWU leadership saw investing in student housing to attract and retain students as critical. Numerous research studies, such as one conducted by Bucknell University in 2020, indicate that a vibrant college residential community positively affects student retention and influences student satisfaction. Outmoded facilities present challenges to meeting modern student life demands, ranging from dining to housing and social collaborations. Studies affirm that “the availability of on-campus housing, especially modern and comfortable facilities, can significantly influence where students choose to attend college” (McClellan and Baum 2022, 45).

TWU witnessed how the shift to remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic significantly affected students’ sense of belonging and the overall college experience. This disruption underscored the value students place on on-campus, in-person experiences. With TWU’s desire to cast a long-term vision for student life while addressing the immediate impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, the university sought input to guide its decision-making regarding the residential area of campus. TWU issued an initial request for proposals to create a plan to replace outdated housing that had exceeded its life expectancy. Little Diversified Architectural Consulting’s (Little) response to the request, which outlined a more holistic vision that expanded beyond student housing alone, led TWU to rethink its approach.

To begin the planning process, TWU compiled a Steering Committee Administrative Team of representatives from TWU’s Business Services, Facilities Operations, and Student Affairs, including Housing, and representatives from Little and the university’s owner’s representative, Ramon Guajardo, Jr. of Ramel Company, LLC. Guajardo represented and advocated for TWU throughout the project. When we began examining options for the university, the necessity of a residential life sector “mini-master plan” became apparent. This mini-master plan would fill in gaps in the existing university master plan for on-campus residential life.

Before conducting the residential life project on campus, we stepped back and considered its possible ripple effects, or how one project could transform the entire campus. A well-crafted master plan provides a roadmap for implementing transformative initiatives aligned with broader institutional objectives. TWU’s Steering Committee Administrative Team, the owner’s rep, and Little’s design team—forming the Mini-Master Plan Team—recognized the need for a tactical design sequence to build momentum during the COVID-19 “lull” in on-campus activities. Because master planning efforts can often lose sight of the end goal due to long timeframes and disparate check-ins, the Mini-Master Plan Team continued the forward movement that developed from ongoing collaborative conversations in a condensed timeframe. By breaking this mini-master plan into manageable phases, TWU could ensure strategic alignment while optimizing resources and minimizing disruptions to campus life.

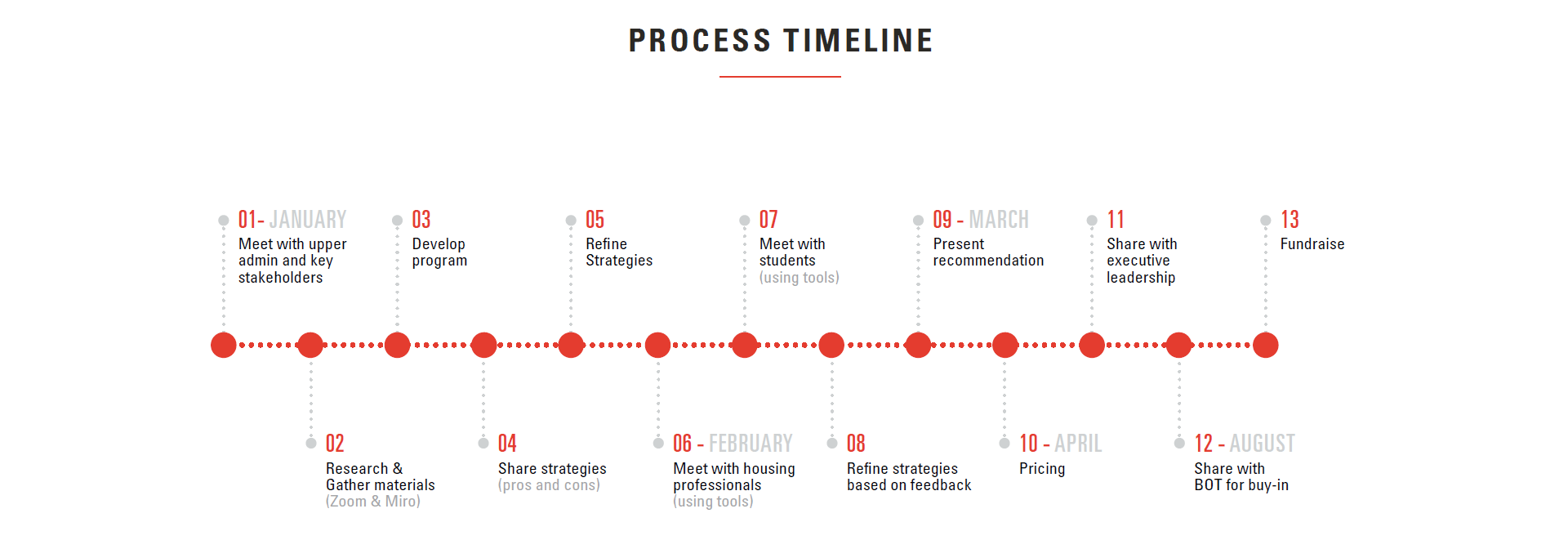

TWU’s Mini-Master Plan Team agreed with this strategy and aggressively approached the project’s timeline. To decide the project’s primary goals, we held conversations, including a visioning session, to determine overlapping priorities among university groups. During these facilitated discussions, we determined “nice to haves” and “need to haves” while responding in real time to feedback from each group.

From these collaborative sessions, the agreed-on goal was to develop and approve a mini-master plan for the campus residential area in fewer than five months. The project included five formal goals:

- Create an engaging, vibrant north precinct of housing and support amenities that would help attract students to TWU.

- Account for the demolition of existing facilities and the potential growth of student enrollment as logically impacted by available beds across several phases.

- Strengthen the connection between the north (residential) and south (academic/support) areas of campus.

- Strengthen the overall campus aesthetic and movement of people.

- Create a unified, community-oriented environment for students who live on campus.

By breaking this mini-master plan into manageable phases, TWU could ensure strategic alignment while optimizing resources and minimizing disruptions to campus life.

INCLUDING STAKEHOLDERS, CONDUCTING RESEARCH, AND CONSIDERING THE BIGGER PICTURE

The project commenced in January 2022, where the initial step was convening TWU’s Mini-Master Plan Team. This crucial phase set the tone for the plan and its phases: it was necessary to understand the visions, expectations, and concerns of those vested in the project. To gather feedback, there was a virtual half-day perspectives session, two days spent on campus, including interviewing students, and the use of a virtual whiteboard service (Miro) to collect and share ideas. The insights garnered were a foundation to guide the subsequent process stages. The key to success for this initial kick-off was convening all essential decision-makers in one room. If a key stakeholder had been absent, the mini-master planning process could have been derailed later. Goal setting comes from careful listening in various types of forums, including in-person conversations and while using digital meeting tools—and asking precise questions of stakeholders and end users.

For TWU, the willingness to involve students proved crucial. Students reacted positively to the opportunity to be involved and shared encouraging feedback about feeling seen and having their needs responded to. It was critically important to hear the different perspectives as to the “why” of the proposed project, and then determine which priorities overlapped. These mutually established goals helped shape future decision-making and served as our mini-master plan’s North Star.

We conducted research and gathered data benchmarks using TWU’s historical information and Little’s work with similar institutions, design best practices, and project cost analyses. Digital, interactive tools such as Zoom and Miro facilitated these efforts, allowing for the project team’s comprehensive understanding of the existing on-campus residential landscape and identifying areas for improvement while maintaining geographic flexibility. Miro was especially vital for this project as it was challenging for team members to meet in person quickly and regularly due to COVID-19. Miro always remained “open,” so all stakeholders could dialogue live for everyone to see, which improved overall communication.

With the groundwork in place, the team developed a robust architectural program—a list of spaces to be included in a building—and desired features and functions that served as a roadmap. This mini-master plan included space sizes for student housing and dining improvements that could be affected by future growth, as informed by initial discussions and research findings.

TWU’s Mini-Master Plan Team recognized the need for a tactical design sequence that would build momentum in the midst of a COVID-19 “lull” in on-campus activities.

SUPPORTING A MULTIFACETED CAMPUS LIFE

During this phase, TWU’s Student Affairs team looked at the entire housing portfolio to better assess broader, overall campus needs and whether the project could help fulfill them. One challenge from our research sessions was that the campus placed significant public spaces inside existing housing to help build a sense of community. While no single building could address everything, we agreed that the new student housing should have meaningful and purposeful amenity spaces to speak to students’ need for community. Dining was an essential plan component because the project involved demolishing the existing housing surrounding the central dining hall. Additionally, it sits at the center of campus. This arrangement presented an opportunity to rethink how TWU’s on-campus dining could better serve residential students and the general student population.

REFINING, REFINING, REFINING

Once we established our preliminary plan, we shared it with additional TWU stakeholders and leadership to assess the pros and cons, a strategy to improve the process through critical analysis. The resulting strategies were refined in March through meetings with housing professionals and during a student workshop. Using collaborative tools of in-person visioning discussions, visual aids, and Q&A sessions, we integrated feedback, allowing the design team to adapt and adjust the plan as needed.

When meeting with TWU’s younger residence life professionals, resident assistants, and students, we shared visual tools they could respond to. We presented images of everything from hallways and public spaces to the living units and bathrooms to gauge what mattered most to stakeholders. While ranking responses as “likes” (green dots) and “dislikes” (red dots) is effective, understanding why someone likes or dislikes a space is more valuable. Contrary to the presumption that a student focuses on individual wants (like their own bedroom and bathroom), the surveyed students were conscious of their evaluation and how it related to cost. Most students surveyed said they highly valued the traditional living experience, which also happens to be the most cost-effective.

The ongoing strategy refinement culminated in a presentation of recommendations in March, marking a significant project milestone. Next, we determined pricing, a critical component that would influence the plan’s feasibility and execution. Subsequently, we shared the refined mini-master plan with TWU’s Executive Leadership in April, securing their endorsement and setting the stage for the final steps of the planning journey.

As April neared its end, we presented the mini-master plan to TWU’s Board of Trustees for buy-in, ensuring the institution’s governance structure aligned with the proposed changes. With the Board’s approval, the final phase could begin, securing the financial resources required to transform the residential area into a space that would truly meet the students’ needs.

WIDENING THE IMPACT THROUGH INTEGRATED PLANNING

Planning for this student housing transformation at TWU was a collaborative effort involving research, wide-ranging stakeholder engagement, and leadership presentations. By soliciting input from students, faculty, staff, and community members, the university and its partners ensured the project was responsive to the needs and aspirations of its diverse stakeholders. The phased rollout of construction activities aimed to minimize disruptions to campus life while maximizing the impact of improvements. Through extensive planning and thoughtful design, TWU has positioned itself for success in an increasingly competitive enrollment landscape, ensuring the university can continue to attract and retain students for generations to come.

What Worked

- Promptly gathering thoughtful, actionable feedback from stakeholders through in-person planning sessions

- Setting a planning schedule that team members committed to uphold

- Including student voices during initial planning phases

What Didn’t

- Anticipating the increased construction costs and their impact on the financial pro forma

REFERENCES

Cacioppo, J. T. & L. C. Hawkley. (2009). “Loneliness and Physical Health.” Annual Review of Public Health 30, 357–373.

Grawe, N. D. (2023). “The Coming Student Shortfall: Demographic Trends and the Future of Higher Education. The Journal of Higher Education, 94(1), 1–25.

Little Diversified Architectural Consulting. (2021). Conversations with College Students: Comfort and Safety on Campus. https://vimeo.com/443376283.

Little Diversified Architectural Consulting. (2021). Conversations with College Students: Remote Learning. https://vimeo.com/438927287.

McClellan, B. E., and S. Baum. (2022). “The coming enrollment cliff: Are your campuses prepared?” Journal of Educational Planning and Administration 41(3), 41–57.